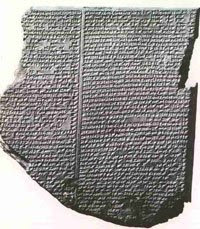

The Epic of Gilgamesh is considered by scholars to be one of the earliest known works of literature. With Sumerian and Babylonian roots that date as far back as 2700 B.C., it is the closest modern readers can get textually into the historic, cultural, and economic beginnings of human civilization. On the surface, Gilgamesh is a story about a selfish and ruthless King who, after a series of trials and misadventures, reforms and becomes a much beloved and virtuous ruler. Underneath, however, the morals and truths the tale conveys reflect a unique code of conduct that society then considered essential to its survival. Amid the unpredictable and little understood forces of nature individuals relied on friendship, craftsmanship, and duty to maintain their fragile existence. Friendship, for example, was not a relationship based merely on platitudes exchanged between two buddies over a drink; rather, it was deemed a collaborative partnership where one had to trust the other to remain consistently vigilant in an environment where any number of hostile beasts or roving bands could appear to threaten their lives. From the perspective of a modern reader, I was struck by a particular passage in which Enkidu, Gilgamesh’s best friend, implies as he lay dying that not only was the killing of Humbaba, the guardian of the forest, needless, but also that having done so ushered the reckless destruction of an entire forest of pine:

“You there, wood of the gate, dull and insensible, witless; I searched for you over twenty leagues until I saw a towering cedar. There is no wood like you in our land. Seventy-two cubits high and twenty-four wide, the pivot and the ferrule and the jambs are perfect. A master craftsman from Nippur has made you; but O, if I had known the conclusion!” (pg 26, Norton Anthology of World Literature).

Gilgamesh and Enkidu embarked on a quest to kill Humbaba solely to secure their legacy as accomplished warriors. For the gain of empty pride the consequence was the wholesale elimination of forest for lavish palaces and public displays of wealth that would soon rot, leaving behind a vast desert. Recent historical evidence suggests that there indeed existed an ecosystem of pine in the Euphrates valley that was wiped out on account of human activity. Today, we face not the clearing of a region of forest, but the eradication of earth’s ecosystems en masse. Ours is the hubris of unchecked industry engaged in a reckless pursuit to extract as much of earth’s resources as current technologies permit. Despite the clamor of the world’s scientific community, we are slow to respond, and for some, even to admit, that soon, ours will be the fate of Enkidu and his people.

“You there, wood of the gate, dull and insensible, witless; I searched for you over twenty leagues until I saw a towering cedar. There is no wood like you in our land. Seventy-two cubits high and twenty-four wide, the pivot and the ferrule and the jambs are perfect. A master craftsman from Nippur has made you; but O, if I had known the conclusion!” (pg 26, Norton Anthology of World Literature).

Gilgamesh and Enkidu embarked on a quest to kill Humbaba solely to secure their legacy as accomplished warriors. For the gain of empty pride the consequence was the wholesale elimination of forest for lavish palaces and public displays of wealth that would soon rot, leaving behind a vast desert. Recent historical evidence suggests that there indeed existed an ecosystem of pine in the Euphrates valley that was wiped out on account of human activity. Today, we face not the clearing of a region of forest, but the eradication of earth’s ecosystems en masse. Ours is the hubris of unchecked industry engaged in a reckless pursuit to extract as much of earth’s resources as current technologies permit. Despite the clamor of the world’s scientific community, we are slow to respond, and for some, even to admit, that soon, ours will be the fate of Enkidu and his people.